How Jane Jacobs revolutionized the way we think about cities

Jul 27, 2021 · 2 mins read

0

Share

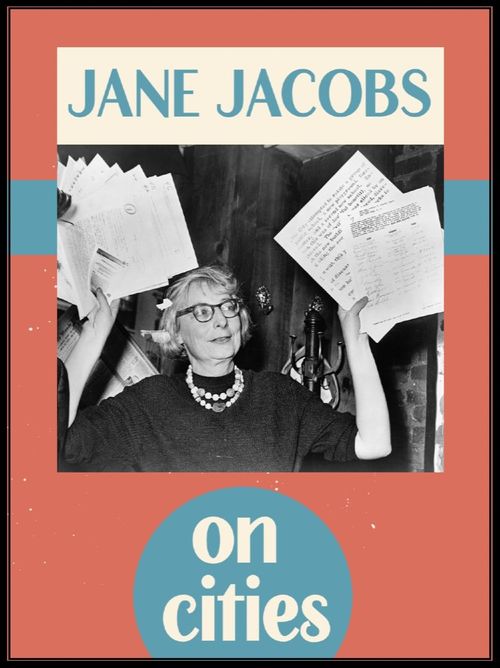

Jane Jacobs didn’t need a degree to know what gives a space its identity. Her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities is considered one of the most influential works ever written on urban living. Why? Because it flew in the face of all convention.

Save

Share

City planning used to be an unquestioned tradition. The methods of engineering streets, bridges, and city blocks were shaped by a tightly knit, exclusive group of thinkers. Jacobs believed their theories did not translate into reality – and she was prepared to call them out.

Save

Share

The dominant style of city planning in the 20th-century was inspired by a man who hated cities. Ebenezer Howard was an English urban planner whose design for a modern metropolis resembled an old-fashioned English country town.

Save

Share

That led to three trendy but flawed models: 1) Garden City (low-rise buildings surrounded by greenery) 2) Radiant City (dense skyscrapers with open land below) 3) City Beautiful (monumental urban centres that would draw people in and promote harmony).

Save

Share

These designs look great on paper… until you realize that a city is more than just attractive buildings and parks. Jacobs saw a direct connection between this blinkered emphasis on style and the crippling of urban vitality.

Save

Share

Jacobs argued that the “vital organs” of a city are its busy sidewalks, for three organic reasons: 1) They’re self-policed, as residents have a shared investment in each other’s safety 2) They provide healthy contact with your neighbors 3) They assimilate children at play.

Save

Share

A park thrives or fails in relation to the variety it accommodates: liveliness attracts more liveliness, whereas emptiness creates a vacuum. That vacuum of functionality is what leads to squalor and crime, Jacobs argued, rather than too many people.

Save

Share

Jacobs identified four “generators” of diversity in urban areas: 1) Mixed primary uses for facilities 2) Small neighborhood blocks 3) Buildings of various ages and structures 4) Population density. These factors are what keeps a city lively and growing.

Save

Share

Through the 1950s and ’60s, Jacobs fought against “urban renewal” plans for her own neighborhood: New York’s Greenwich Village. This put her at war with Robert Moses, the city’s planning czar, and led to a prolonged David-and-Goliath-like struggle over a key part of Manhattan.

Save

Share

Against all odds, Jacobs ultimately succeeded in preserving the Village for the same reasons her writing continues to resonate. Her ideas of what makes cities special were a rebuke to outdated thinking and powerful enough to unite public opinion in the name of community.

Save

Share

0